Twenty-eight years ago, a groundbreaking article in the Harvard BusinessReview articulated a novel idea for how organizationscould “re-engineer” their business processes by using “bank creditcards” to make procurement of low-value goods work better, faster,and cheaper. Since that time, the use of purchasing cards (p-cards)has grown so rapidly that the cards now represent a new normal inthe way North American businesses pay for low-value goods andservices. Market estimates indicate that spending on p-cards hasgrown from near zero in 1990 to more than $350 billionannually.

|Accordingly, commercial issuers have continuously upgraded cardtechnology, including significant improvements in controls tosupport increasing demands for enforcement of spending policies.More recently, issuers and technology providers have promoted theconcept of transforming accounts payable (A/P) from a costcenter to a profit center, principally by improving liquidity,reducing manpower, and obtaining card-issuer incentive cash.

|These trends notwithstanding, our research over 25 yearsindicates that although the p-card value proposition remains trueand valid, significant challenges to successfully implementing ap-card program continue to reduce the benefits companies areactually achieving. The overall p-card market in North America isrobust, but a high proportion of that spending is conducted by onlya small fraction of p-card adopters.

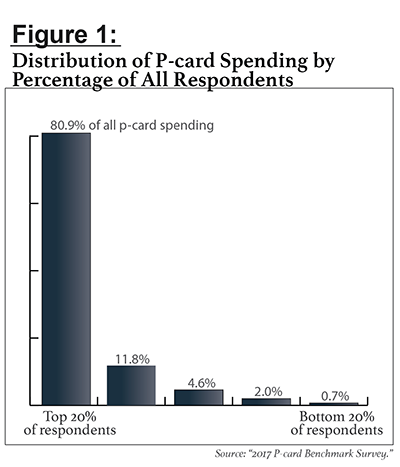

| In general, in any industry orcompany size category, a small segment of card-using organizationscomprise the bulk of spending. Across our 2017 survey, we found an80:20 pattern. (See the sidebar About the Survey,below.)

In general, in any industry orcompany size category, a small segment of card-using organizationscomprise the bulk of spending. Across our 2017 survey, we found an80:20 pattern. (See the sidebar About the Survey,below.)

As Figure 1 illustrates, 20 percent of survey respondents wereresponsible for 80.9 percent of the total spending reported acrossall participants. In fact, the top 40 percent of respondentsgenerated 92.7 percent of total p-card purchases, while the bottom60 percent generated only 7.3 percent of spending. A similarpattern exists within each market segment, as determined by companysize or industry.

|The root causes of p-card program underperformance are a matterof speculation, but it is safe to say that many organizations,after making the decision to adopt card-based payments for goodsand services, have found the implementation to be challenging. Inthis respect, the implementation of p-card programs is similar toother major technological changes, the majority of which fail todeliver the promised value.

||

Benefits of an Effective Card Program

The argument for the use of p-cards is compelling. Surveyrespondents indicated expectations that a p-card program couldprovide:

- Savings on transaction costs.Respondents estimated that the administrative cost of procuring andpaying for a good or service is 78 percent lower when the purchaseis made using a p-card, falling from $89.99 per transaction via atraditional, paper-based purchase order process to $20.14 for atransaction via p-card.

- Process simplification. According toour 2014 p-card survey, the traditional purchase order methodrequires an average of 2.3 approvals for a $2,000 payment, while asimilar p-card-enabled transaction requires only 1.4 approvals (a39 percent reduction).

- Increased working capital. A typicalp-card transaction provides 29 days of float; the working capitalsavings associated with p-card purchases are equivalent to a 0.4percent discount on the price of the purchased goods andservices.

- Cycle time savings. The averageprocurement cycle time—from need identification to receipt ofgoods—is 71 percent shorter when the transaction is paid for usinga purchasing card. Our survey indicates the procurement cycle is9.9 days via the traditional purchase order-based process but only2.9 days via p-card.

- Rebates. The vast majorityof card-using organizations (82 percent) received a rebate forp-card spending in the past year. Organizations that do get arebate spend significantly more via p-card and direct more of theirlow-dollar transactions to the p-card for payment.

- Other benefits. P-cards also lead toless reliance on checks, discounts based on p-card data, reductionsin petty cash accounts and cash advances, and the avoidance of latefees or lost discounts.

Any reduction in procurement costs that a p-card program cangenerate will boost the organization's bottom line, directlyincreasing net income.

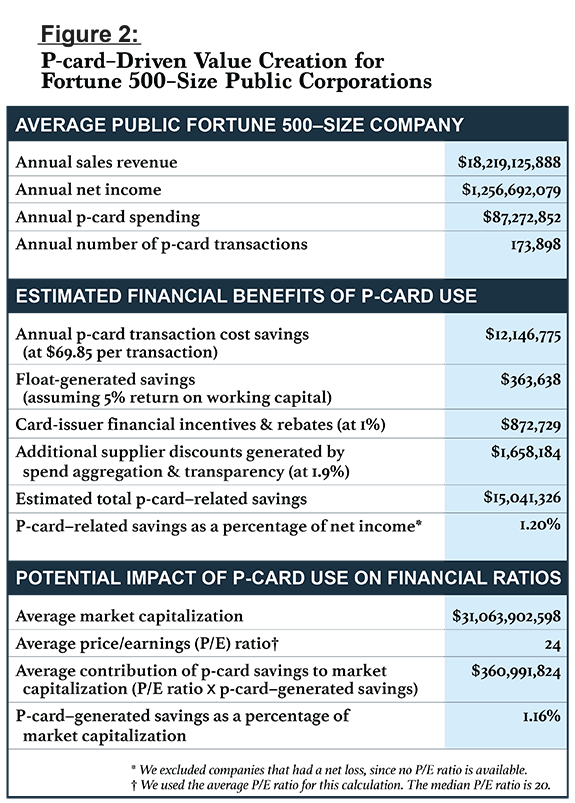

|To highlight this effect, we analyzed net income and marketcapitalization figures, along with p-card savings, for the publiclytraded Fortune 500–size companies represented in thesurvey.1 Figure 2 shows that these companies have, onaverage, annual revenue of $18.2 billion, and they spend an averageof $87.3 million on p-cards annually. As a result of this spending,the average company generates annual cost savings of $15 million,which improves corporate profitability by 1.2 percent. The $15million savings figure is an ongoing annual realization of theefficiency of the procurement process, not a one-off savingsevent.

|

Figure 2 extends the analysis further, to estimate the impact ofp-card–generated savings on the company's market capitalization.For this calculation, we multiplied the savings by the company'sstock price–to–earnings, or P/E, ratio. The result of thiscalculation reflects the impact of p-card savings on the marketvaluation of the company. As Figure 2 demonstrates, ongoingp-card–related savings—which directly impact net income—seem todeliver an increase in market valuation that averages 1.16 percentfor Fortune 500–size corporations.

||

Is Your Card Program Underperforming?

An underperforming p-card program is one that fails to meetorganizational expectations with regard to transaction costsavings, cycle time savings, process simplification, reduced needfor working capital, rebates, or other benefits. Most organizationsfocus on the full complement of value attributes but pay particularattention to administrative cost savings, float, and financialincentives (e.g., cash back) provided by the card issuer.

|A common problem among underperforming card programs is amisdiagnosis of performance, which delays remedial actions toincrease p-card value. Our research shows that for 86 percent ofcompanies whose programs are shown to need improvement based onperformance metrics, management has a perception of programstrength that is inconsistent with market data.

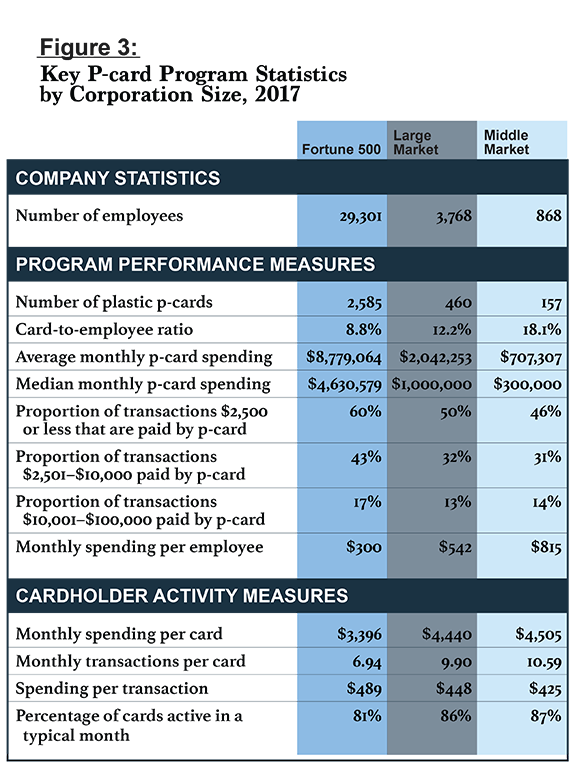

|As a first step to optimize p-card performance, an organizationshould obtain access to benchmark market data about p-card use inorganizations of a similar size and type. It should compare andevaluate its own program against this benchmark data. Figure 3, forexample, provides spending and card distribution norms for morethan 1,300 corporations that responded to our 2017 survey. We'veseparated the data by company size: Fortune 500–size, which equatesto annual revenue of $2 billion or more; “large market,” whichreflects annual revenue between $500 million and $2 billion; and“middle market,” with annual revenue between $25 million and $500million. Similar benchmarks are also computed by industries inwhich the organization operates.

|

In addition to comparing their card program against industrybenchmarks, executives can stay on the alert for common signs thattheir p-card program is failing to live up to its potential.

|The first and foremost sign, of course, is that spending on thep-card is comparatively limited. Yet an underperforming programsends out many other signals as well. Here are a few to watchfor:

- Organizational leaders do not measure or evaluate the progressof the p-card program.

- Accountability for program performance is not maintained,and/or success is not rewarded.

- Employees complain that the p-card is not suited to theirspending needs.

- Employee spending behavior indicates a lack of training orknowledge of p-card policy.

- Employees are opting to continue to use the old process.

- Management is overly focused on the potential for p-cardmisuse.

- The p-card program is static; it is not evolving to reflectchanges in the commercial card market.

- P-card data is poorly integrated with other systems in theorganization.

- Traditional processes—such as maintenance of receivingdocumentation when goods are delivered to cardholders—are simplymigrated to the card-based process, rather than being redevelopedfrom the ground up.

- Signs of noncompliant p-card spending activity are poorlymonitored, and disciplinary actions are too weak to facilitatenecessary control over the process.

- Supply chain partners have not been brought into p-card paymentprocesses.

|

Causes of Underperformance

Failure to launch a successful p-card program can typically betraced back to a series of missteps that coalesce to undermine cardvalue and/or use. We break these reasons into three categories:acceptance, control, and technology.

|The most common reasons why p-card programs languish or declineare:

|

Issues Around Acceptance by the Organization and ItsSuppliers

- Management does not publicly support or articulate a compellingand inspiring reason for p-card use.

- The scope of the p-card activity is limited to a subset ofgoods and services.

- Resources are inadequate for effective programadministration.

- The organization has not developed and disseminated clearpolicies and guidelines for p-card use.

- The organization does not adequately train employees on p-carduse.

- The organization has not developed, or does not measure, keyperformance indicators to evaluate the progress of the p-cardprogram.

- P-card use is not mandated for a defined group of purchaseactivities.

- The organization does not have a supplier-enablementstrategy.

- The organization has only limited engagement with suppliers tolower the cost of card acceptance.

Issues of Control

- Management is more concerned about potential card misuse thanabout achieving the benefits of card use.

- Card distribution is limited to a small sect of employees(typically managers).

- Spending limits do not support the cardholders' actual buyingneeds.

- The organization does not deploy controls in a way thatinspires confidence among managers.

- Executives are uncomfortable with the level of detail providedabout purchases, even if the need for additional detail isunclear.

- The company does not adequately monitor card use, or potentialmisuse (e.g., unusual purchases).

- Program organizers have not implemented adequate riskmanagement, such as acquiring insurance against misuse ofp-cards.

- Policy fails to clearly describe which card purchases areallowable and which are not allowed.

- Disciplinary policy does not embody a strong deterrent to cardmisuse or lax supervisory oversight of p-card spending.

Issues of Technology

- Card data is not completely integrated with accounting orexpense management systems.

- The organization has not explored other creative cardtechnology options, such as virtual cards.

|

A Roadmap for Program Rehabilitation

Few technology implementations fully meet every expectation, andp-card programs are no exception. There is a “chicken or the egg”quality to the p-card implementation challenge. Specifically,poorly implemented p-card programs deliver little value in theirearly stages. Improving the program's performance will requirep-card spending to increase, but if the program isn't performing,management may deem it unworthy of continued investment.

|The solution lies with information and education. Through morethan 20 years of discussions with administrators ofhigh-performaning p-card programs, we have identified nine specificsteps that companies can take to transform a lethargic p-cardprogram into a program that delivers significant benefits.

||

1. Assess the current state of the program, andreview the choices that got you there. Objectivelyassess the current state of your p-card program, usingindustry-specific benchmark norms and well-recognized best practiceconfiguration options.

||

2. Find yourcommunity. No need toreinvent the wheel. You can get insights from other organizationsin the same industry that have overcome barriers to achievesignificant and enduring value from p-card use. Seek out thisinformation through interactions at card-industry conferences andby using benchmarks.

||

3. Address the fear. Educate yourorganization's leadership team to overcome the fear factor. Manyexecutives operate in a preternaturally defensive mode, focusing onwhat can go wrong. Card program managers must clearly communicateto management each aspect of the p-card value proposition and everylever of control over cardholder activities. Use data to assess therisks of card misuse, and to weigh those risks againstorganizational benefits from card use. Have an action plan in placeto mitigate the effects should a misuse event occur.

||

4. Create a “safe space” for p-card use andexperimentation. No one will support a program thatlacks proper controls or fails to comply with organizationalpolicy. The most effective route for change is to bring knownp-card control configurations to the attention of compliance andcontrol advocates in the organization (e.g., internal audit) forreview and critique.

||

5. On-board employees. Employees maybe hesitant to jump on the p-card train. Consider acard-distribution policy that prioritizes those individuals whowould benefit most from a card, thus creating card evangelistswithin the organization. Their enthusiasm for the simplicity andbenefits of card-enabled purchases may convince others in theorganization to want in.

||

6. Exploit technology. Card datashould integrate seamlessly with organizational data; work withyour issuer to make that happen. Technologies like data mining notonly highlight growth opportunities, but also strengthen controlover card use, providing greater comfort to management and users.Meanwhile, virtual cards and mobile applications open awhole new terrain for card capture of spending.

||

7. Set targets. Define the goals forthe p-card program, which may include reductions in cycle timeand/or headcount. Regularly measure performance tied to thosegoals. Develop policies that encourage p-card use as the company'spreferred payment option.

||

8. On-boardsuppliers. If card users report thatsuppliers are reticent to accept card payments, start a dialogue toinform suppliers about how they can benefit from supporting greaterp-card use by your employees.

||

9. Report progress, and celebratesuccess. Communicate the p-cardprogram's progress toward the goals set forth, as well as anycourse corrections. Celebrate the successes.

||

While corporate p-card spending around the world continues tooutpace the growth of national economies, many programs areunderperforming, as casualties of a flawed implementation strategy.Organizations that fail to compare their program's progess againstbenchmarks will have limited ability to see implementationproblems—and so limited ability to take corrective action.

|Effective card-program implementation is built on fundamentalcomponents of p-card value: internal and external acceptance ofcards, appropriate program controls, and leveraging availabletechnology. Based on our data, many companies drive significantdollars to, and reap significant rewards from, p-card purchasesbased on attention to these fundamentals. However, initial p-cardimplementation efforts often fall short of expectations.

|Champions of p-card programs that do not compare well againstindustry norms can and should take the basic steps necessary to gettheir programs back on track. Such an intervention is well worththe effort, because continued growth of a p-card program has thepotential to deliver notable value to the organization.

||

1. NOTE: We focused on Fortune 500-size public companiesbecause of data availability. To provide a representative look atorganizations in this group, we removed businesses that areanomalistic, either because annual revenue is unusually large orbecause p-card spending is either unusually large or small relativeto the rest of the group.

|

Dr. Mahendra Guptaserves on the faculty of the Olin School of Businessat Washington University in St. Louis, where he is theGeraldine J. and Robert L. Virgil Professor of Accounting andManagement. His research has been published in leading academicjournals. He has served on several editorial boards and has been afrequent speaker at research workshops and conferences worldwide.Gupta has been a consultant to various firms and governmentagencies and serves on various corporate and not-for-profitboards.

Dr. Mahendra Guptaserves on the faculty of the Olin School of Businessat Washington University in St. Louis, where he is theGeraldine J. and Robert L. Virgil Professor of Accounting andManagement. His research has been published in leading academicjournals. He has served on several editorial boards and has been afrequent speaker at research workshops and conferences worldwide.Gupta has been a consultant to various firms and governmentagencies and serves on various corporate and not-for-profitboards.

Richard J. Palmer isa professor of accounting and Copper Dome Faculty Research Fellowat Southeast Missouri State University. He is a frequent speaker atcommercial card conferences and the co-author of numerous articlesabout industry use of e-procurement tools and bank commercialcards. Palmer's insights on card use have been quoted in popularNorth American news outlets such as the Wall Street Journal, ABCNews Good Morning America, CNN Money, and CBS NewsMarketWatch.

Richard J. Palmer isa professor of accounting and Copper Dome Faculty Research Fellowat Southeast Missouri State University. He is a frequent speaker atcommercial card conferences and the co-author of numerous articlesabout industry use of e-procurement tools and bank commercialcards. Palmer's insights on card use have been quoted in popularNorth American news outlets such as the Wall Street Journal, ABCNews Good Morning America, CNN Money, and CBS NewsMarketWatch.

Complete your profile to continue reading and get FREE access to Treasury & Risk, part of your ALM digital membership.

Your access to unlimited Treasury & Risk content isn’t changing.

Once you are an ALM digital member, you’ll receive:

- Critical Treasury & Risk information including in-depth analysis of treasury and finance best practices, case studies with corporate innovators, informative newsletters, educational webcasts and videos, and resources from industry leaders.

- Exclusive discounts on ALM and Treasury & Risk events.

- Access to other award-winning ALM websites including PropertyCasualty360.com and Law.com.

*May exclude premium content

Already have an account? Sign In

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.