There is an old folk tale about two frogs: One lives on the edgeof a deep, secluded pond. The other lives on the edge of a shallowpond near a country road. The first frog exhorts his friend torelocate; if he stays in that shallow pond, bad things will happen.But that second frog stays because he is afraid to abandon what heknows—however uncomfortable or unsustainable it might be—for theunknown.

|Soon after, disaster befalls the frog of the shallow pond. InAesop's telling, a wagon comes by and crushes the frog. In anotherversion, the shallow pond dries up, leaving the frog to bake in thesun. And in another version, because the shallow pond is so easy toreach, lots of additional frogs move in, and they soon eat all theflies and collectively starve. The end result is always the same:Those who are unwilling to face change invite self-destruction.

|A McKinsey & Co. report in 2013, “Agents of the Future: TheEvolution of Property & Casualty Insurance Distribution,” seemsto echo this parable. McKinsey identifies the usual suspects thatspell supposed doom for any agent or broker selling personal linesinsurance: increasing product commoditization; a rise ofmultichannel distribution (at the expense of traditional wallsbetween older product channels); a desire among customers to buydirectly from the carrier—and an increasing willingness of thecarrier to accommodate them. “There are signs that the economics ofthe traditional agent model are beginning to unravel,” McKinseywrites, suggesting that perhaps the personal lines pond had toomany frogs and not enough flies.

|But is that really the case? Not everyone thinks so.

|Chasing the 'Golden Egg'

|The Hanover Insurance Group directs a lot of energy towardsupporting its exclusively independent agent distribution system,rather than concentrating on selling personal lines directly, asother national carriers might. This gives the company a keen senseof how independent agents are approaching personal lines, says DickLavey, executive vice president, president of personal lines andchief marketing officer for The Hanover.

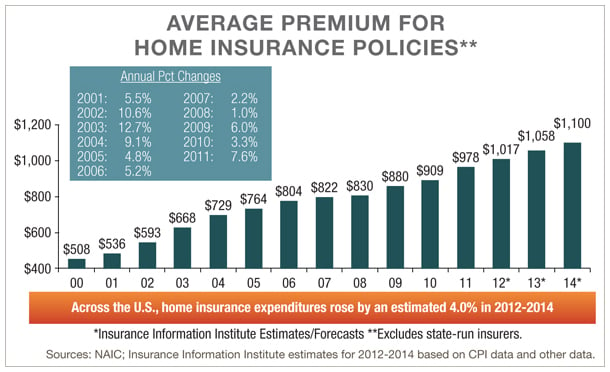

|“The whole independent agent channel is thinking more aboutpersonal lines than before,” Lavey says, pointing out that onaverage, commercial lines tend to have a 20% EBITA (earnings beforeincome, taxes and amortization) margin. For personal lines, it iscloser to 30% because personal lines is what he calls a “sticky”business. All of the direct-sales efforts in the world won't changethe fact that if the average personal Auto or Homeownerspolicyholder's bill looks pretty much the same as it did last year,most policyholders have little incentive to switch carriers. Inmany cases, it's just not worth the hassle.

||The trick, Lavey says, is to chase what he calls “the goldenegg”—the combination of Auto, Homeowners and other personal lineswithin the same client. The public isn't thrilled about actuallybuying insurance, however, and price alone won't win the day, sovalue-added services must be considered—such as phone apps that letyou take video inventory of your house and store it on the cloud tospeed claims, or services that send recall notifications or makeand model news based on your vehicle identification number.

|“We're trying to create services the customer wants, to bringHomeowners and Auto together,” says Lavey. “That makes them feelattached both to the carrier and the independent agent who providedit all.”

|Not all innovations are pure upside, though, says Gavin Blair,chief product officer for personal lines at The Hanover. Take smartwindshields and collision detection, two safety measures thatautomakers are introducing to help prevent collisions. While Blairhasn't yet seen such things reduce the frequency of accidents, heworries that when there is a loss, it will be more severe. “Thosesensors are expensive,” he says. “A minor fender-bender couldbecome a $6,000 event just to fix a camera.”

| Blair also notes that the falling price ofgasoline isn't likely to help personal Auto, either. As gas getscheaper, people drive more. Those carriers who only sell personalAuto may see a lot more miles driven, and correspondingly, moreaccidents.

Blair also notes that the falling price ofgasoline isn't likely to help personal Auto, either. As gas getscheaper, people drive more. Those carriers who only sell personalAuto may see a lot more miles driven, and correspondingly, moreaccidents.

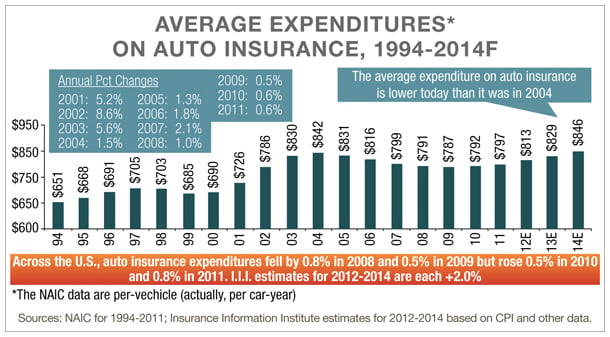

Telematic devices, like Progressive's Snapshot, which driversvoluntarily plug into their cars to transmit back to their insurersdriving data, such as average speed, braking tendencies andsharpness of turn, can be used to price risk more effectively. Andin areas such as commercial Trucking, Blair says that the “sentineleffect” of knowing somebody is studying how you drive can imposesafer driving habits. But it hasn't caught on in the personalspace. The telematic devices themselves cost about $90 each and thecost of data transmission is another $50 to $60 a year, in additionto the cost of shipping the devices out to customers. All this, forAuto policies that on average cost around $1,000 a year. The ROIjust isn't quite there yet.

||What's more, many people just don't like plugging Big Brotherinto their cars. Ironically, they are more likely to permit thesame transmission of data from their smartphones or wearable tech,Blair says—so until insurers get policyholders to install telematicapps (which he believes could do a lot of good with the teenmarket), the promise of telematics might not yet be fullyrealized.

|New Dawn for Independents

|Brian Cohen, an operating partner at Altamont Capital Partnersin Palo Alto, Calif., brushes off the notion that personalAuto—which accounts for some 70% of the total personal linesmarket, is on an inevitable march toward direct sales and totalcommoditization. “People point to the U.K. as an example of whatshould happen here,” Cohen says, referring to how the personal Automarket in the U.K. has gone almost entirely direct, mostly soldthrough the Internet. But, he adds, that's only because carriersthere can change prices at a moment's notice (they don't have tofile with America's 50 different Departments of Insurance), and sothey can race to the bottom on price.

| Agency-based carriers still dominate thepersonal lines market, Cohen says, and when it comes to using theInternet to drive sales, it's the agents who use it best, employingConstant Contact, Google ads or other digital marketing tools toget their names in front of their local micro-markets where theycan sell most effectively. Using real-time raters to produceinstant quotes for curious online shoppers—quotes that also directthem to their local agent—further maintain the agent's relevance ina digital world. So much for the comparison of today's insurancedistribution to yesterday's travel agents.

Agency-based carriers still dominate thepersonal lines market, Cohen says, and when it comes to using theInternet to drive sales, it's the agents who use it best, employingConstant Contact, Google ads or other digital marketing tools toget their names in front of their local micro-markets where theycan sell most effectively. Using real-time raters to produceinstant quotes for curious online shoppers—quotes that also directthem to their local agent—further maintain the agent's relevance ina digital world. So much for the comparison of today's insurancedistribution to yesterday's travel agents.

As one example, Cohen points to CompareNow, a direct writerstarted in the U.S. by U.K. insurer Admiral. “They thought they'dkill it here,” Cohen says. “They got lots of press, but they havehad no measurable impact in terms of volume. If you go to theirsite, it looks great, and you think that this should work. But itjust doesn't.”

|The other thing to look at, Cohen says, is that all of thepressure in personal lines is really on the captive agents. In aworld where consumers expect multiple buying choices foreverything, getting a single quote from a single insurer just won'tcut it. They expect multiple quotes that the captive agent justcan't provide. And they need a professional to advise them on whatthe trade-offs are when choosing one carrier over another.

||What makes things worse for captive agents, Cohen says, is therise of the agent aggregator, a kind of field-marketingorganization that represents several hundred independent agentsunder a single umbrella, and are very good at seeding Googlesearches on insurance products with links that lead back to them.According to Cohen, aggregators are luring established, successfulagents away from captive insurers with the promise of upside salespotential that comes with access to multiple carriers, whileoffering them the same kind of support they might have enjoyedwithin a captive system.

|“Aggregators aren't enlarging the pie,” Cohen says, “they'rejust shifting the most productive agents from the captive to theindependent channel. This is new. For several decades, you saw thenumber of independent agents dropping and captives rising. Now,that is starting to switch.”

|Aggregators might be the least of carriers' concerns. Personallines remains an incredibly competitive market, especially withrock-bottom interest rates giving insurers no choice but to maketheir money on underwriting profit, which is far easier said thandone. Cohen notes that many carriers are writing unprofitablebusiness just to maintain their market share in the face ofinternecine pricing from competitors. This is especially true wherecarriers are doing whatever they can to lock in both a customer'spersonal Auto and Homeowners business, that “golden egg” that Laveyat The Hanover referred to previously.

|The good news is that because reinsurance is so incredibly (somewould say excessively) abundant right now, insurers can writecoverage more cheaply and hedge that extra risk on their books bynegotiating very competitive reinsurance treaties. But thechallenge remains for personal lines writers to grow profitably,and the key there, Cohen says, is to target niches. That too, isn'teasy, because most carriers are already using big data andanalytics to identify potentially profitable markets—such asmotorcycles, recreational vehicles and light watercraft. For most,the answer to profitable growth might just come down toacquisition.

|Homeowners is more of a free-for-all, where big carriers facesubstantial concentration of risk in coastal areas stretching fromMaine to Texas. A lot of them don't really want to write there,Cohen says, which is giving an opportunity to smaller, moreaggressive writers who are taking advantage of cheap, plentifulreinsurance to go where angels fear to tread.

||A great example of this is California, “which was almost afour-letter word when writing property,” says Cohen, thanks toevery kind of anathema to a homeowners book—mudslides, earthquakes,wildfires. But loss data shows that the California property markethas actually been profitable for the last 20 years, Cohen adds,which is drawing in aggressive new players to that market.

|And it's not like big carriers can trade on their brandrecognition. “'Like a good neighbor' doesn't resonate like it did20 years ago,” Cohen says, thanks to public distrust of biginstitutions—especially insurance carriers—following the post-2009financial crisis. This enables smaller, nimble carriers topenetrate markets in ways they never could before—and it gives anindependent agent willing to do some homework on those carrierstargeting niche markets a competitive advantage over theirpeers.

|“The big headlines are that if you're in personal lines, you'rein a dying area of the insurance industry. In fact, you are not,”Cohen says. “If you are an independent agent focusing on personallines, there are incredible opportunities today that weren'tavailable 10 or 20 years ago. You have to look at your market andyour business in a different way than you might have in the past.If you do that, this is the new dawn of the independent agent. If Iwas entering the industry and thinking about where I would want tobe on the distribution side, I would want to be an independentagent.”

Want to continue reading?

Become a Free PropertyCasualty360 Digital Reader

Your access to unlimited PropertyCasualty360 content isn’t changing.

Once you are an ALM digital member, you’ll receive:

- All PropertyCasualty360.com news coverage, best practices, and in-depth analysis.

- Educational webcasts, resources from industry leaders, and informative newsletters.

- Other award-winning websites including BenefitsPRO.com and ThinkAdvisor.com.

Already have an account? Sign In

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.